The Northern Nigerian village of Lauki is far away. It is far from the state capital of Bauchi, far from hospitals, far from schools. It is a 45-minute rough, dusty drive from the main paved road.

And yet Lauki has become a destination for hundreds of Nigerians who were forced from their homes by Boko Haram and are trying to rebuild their lives in this remote village.

Reaching displaced children can be challenging as their families move around or settle in far-flung places recommended by family members, former neighbors and friends. And sometimes, getting host communities to welcome and accept new additions can take convincing.

That is not the case in Lauki, where the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Education Crisis Response Program is finding ways to create greater access to quality education for displaced school-aged children. While the program has brought training and resources to the community, it is residents who stepped up to actually build a school.

“This is where you see the community come together to say, ‘This project has shown to us that you can actually come together and build a small center that will allow our children to have access to education.’ And they went ahead and did that,” says Ayo Oladini, the Program Director.

“That is huge,” he says. “And it’s inspirational.”

USAID’s Education Crisis Response program is implemented by Creative Associates International, the International Rescue Committee, state governments and local organizations.

“The ownership of the non-formal learning centers can only be realized if you allow communities to be involved and to participate.” Ayo Oladini, Director, Nigeria Education Crisis Response program

A community contribution

The Education Crisis Response program works in Bauchi and four other Northern Nigerian states to bring literacy and basic math courses and psychosocial support to more than 54,000 students through more than 1,100 non-formal learning centers.

USAID’s program is designed to reach displaced children who have scattered across Northern Nigeria, whose educations have been disrupted and futures put on hold.

But in remote places like Lauki, bringing new opportunities for learning benefits host and displaced children alike. School-aged children and youth from Lauki were walking up to five kilometers each way to class. With no nearby options, many families chose not to send their children to school at all.

“We understand we were backward educationally,” says Alhaji Musa Galadima, Lauki’s Village Chief. “The schools around us are far; whenever we asked children to go to school, they are discouraged…by the distance.”

When Education Crisis Response program came to Lauki, it connected community groups into coalitions, and advised them on education advocacy and coalition building.

“The ownership of the non-formal learning centers can only be realized if you allow [communities] to be involved and to participate in…the process,” says Oladini.

A committee of residents and local leaders always determines the learning center locations. And community coalitions comprised of local organizations make action plans to support education for internally displaced students.

Brought together by the program and informed about the power of collective action, these community coalitions also identify people to be trained as facilitators, take responsibility for protecting internally displaced children from abuse or stigmatization and mobilize the community to support the center with school materials.

Members of 42 such coalitions in the three states learned about “Do No Harm” principles that could help guide them as they shape the experience of displaced children in the new non-formal learning centers.

Master trainers selected and prepared by the program and its state and local partners will also help them think through the Community Action Cycle—an approach that empowers the community to identify both problems and solutions.

We can all see its results

Mohammed Fawa serves as the Chairman of the Community Coalition. He says the members received in-depth training on the importance of coming together and supporting those in need, especially internally displaced persons.

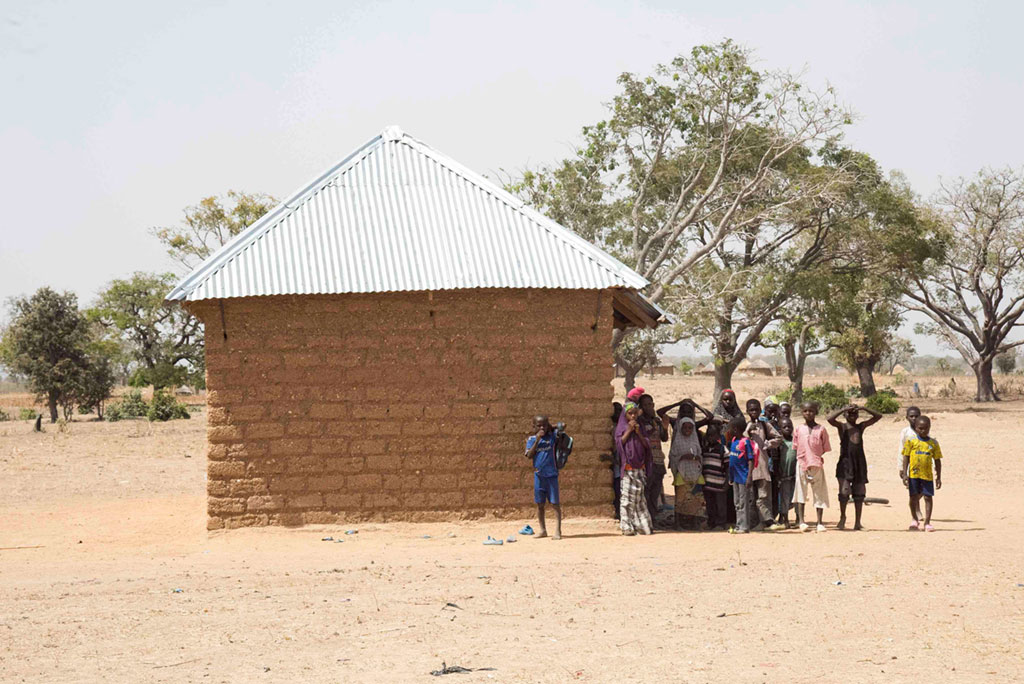

But with about 50 young students trying to learn under the shade of a tree, the coalition realized they could contribute to a much more effective learning environment.

Coalition members visited with traditional leaders and advocated across the community for building a non-formal learning center that would benefit host and displaced children alike.

“What encouraged us was [that] right from the beginning when the school started there was no structure. Yet, [the program] came and established schools; identified and trained teachers; provided teaching and learning materials; and the children were provided with meals,” Fawa says. “If somebody could come from far away country to give you these huge supports, courtesy demands you do something to show your appreciation. This was why we thought to do something as a community’s contribution.”

On top of the advocacy and community sensitization, coalition members pitched in on the actual construction of the center.

“There was difficulty in having total class control when we were studying under tree shades,” says Dahim Mahmoud, a Facilitator in Lauki’s non-formal learning center. Now, Mahmoud says he has the children’s full attention.

Now that classes are up and running, community coalition members continue to visit the school and meet with facilitators to see what other help they can provide.

The community coalition’s work, and the program’s inclusive and effective curriculum, has already achieved what Fawa calls a “major victory”: For the first time, 30 students from Lauki’s primary school took the upper basic exams. All of them passed and enrolled.

“This impresses me and gives me pleasure and assurance that our work has been a success,” Fawa says.

For now, these students will have to travel each day to get to an upper basic school. But Fawa points out that the community intentionally built Lauki’s new learning center much larger than it needed to be for the program’s purposes.

“You might have noticed the size of the structure is big,” he says. “This is because we do not know what will happen next.”

If this community has its way, they will continue to advocate for education for children who are new to Lauki and for children who never left home. They hope to turn the school into an upper basic or even secondary school—allowing children from the far-flung town to continue their education in a way never before possible.

“We do not want the schooling to come to an end, even after the project,” Fawa says. “My call to our people is, let them consider what we did as a lesson. Because it is only a meager amount, yet we can all see its impact.”

Reported from Nigeria by Michael J. Zamba and Aishatu Aminu.