Dar es Salaam, Tanzania—The bookshop is dim and hushed, empty just a few minutes after opening time on a Sunday morning. It’s my last day in Tanzania, and what better way to spend a spare hour in Dar es Salaam than with a quiet dip among the shelves of poetry, photobooks and fiction.

Climbing the little staircase down from the second-floor stacks, I hear a noise escape from a back corner. A giggle. Peering through the slats, I see two small children tucked up into their mother’s sides as she reads them a storybook.

Her Kiswahili words are foreign to me, but the scene is familiar. I spent a childhood on my mother’s knee—my sister occupying the other—listening to her read tales with names like “The Mountains of Tibet” and “Pickle Chiffon Pie” until we were old enough to proudly read them to ourselves.

From first to fifth grade, I went to a school where the classrooms were arranged in a circle around a library full of books for us to read there or take home: books formed the literal center of my world.

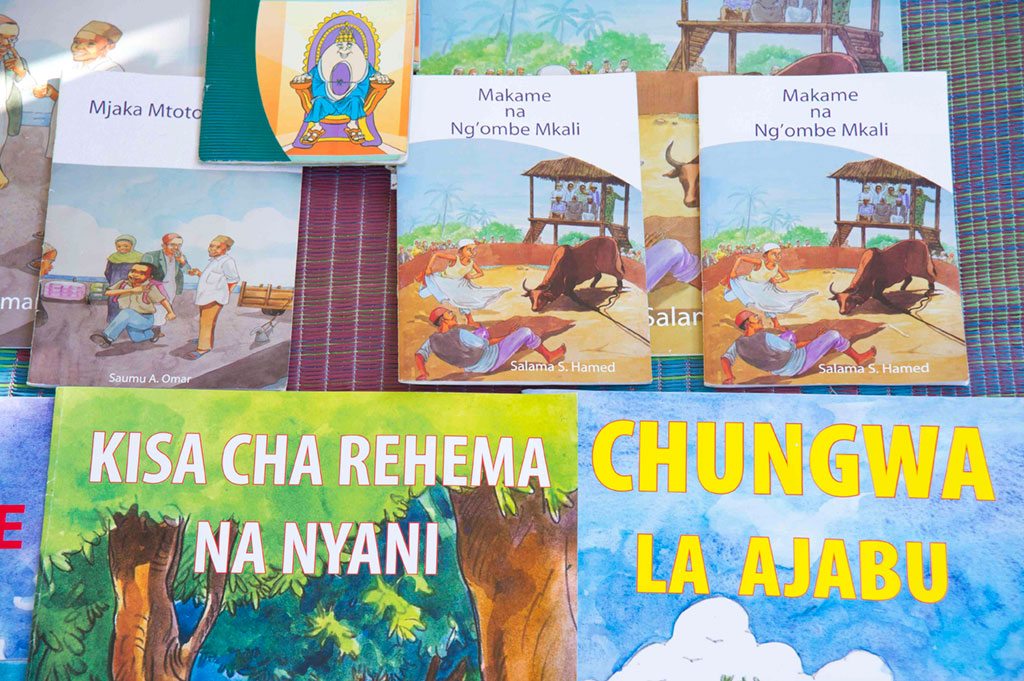

But during the past week I spent traveling from Dar es Salaam to the islands of Zanzibar and down the coast to overgrown Mtwara, I’ve come to see how rare this morning bookshop scene is. Most children in Tanzania do not have ready access to books at all, let alone age-appropriate reading materials in their own language, festooned with colorful illustrations.

That’s one of the reasons Creative’s Tanzania 21st Century Basic Education Program involved local publishing company Children’s Book Project in its efforts to get more books into 900 primary schools.

The Children’s Book Project had been publishing children’s books since 1991. But there was still an acute shortage in schools and public libraries, and it shows: illiteracy among students in primary schools remains too high, according to Executive Secretary, Pilli Dumea, who said children are failing tests because they can’t read the questions.

To her, that’s a failure that starts from teacher training, which does not include courses on teaching and supporting reading.

“They take reading as something that can be developed; it can come naturally,” says Dumea. “Well it’s not.”

Research agrees with Dumea: “The ability to read and write does not develop naturally, without careful planning and instruction,” according to U.S. literacy initiative Reading Rockets. “Children need regular and active interactions with print.”

Creative’s program has worked with the Children’s Book Project produce more grade-level books—shorter books with fewer words on each page, and books with text large enough for a teacher to easily read out loud as his or her charges look on.

The Children’s Book Project participated in training aimed at teachers so it could align its books with the same phonics-based reading instruction that has proven effective in improving literacy among primary school students.

It also helped set up reading tents: outdoor spaces strung with published titles and handmade books that students write and illustrate themselves based on stories they’ve read or heard. Children who read here learn that reading is fun, and find encouragement to make it a habit.

In the reading tents I saw in each school I visited, children pulled their favorite stories off the makeshift shelves and sat on plastic mats on the floor, absentmindedly wriggling their bare toes as their fingers traced the new and familiar words.

These young students have the chance to take library books home with them, and the Children’s Book Project is continuously trying to add new titles to its collection of Kiswahili-language offerings. Not all of their parents can read to them like the mother in the bookstore did, but now they can have the pleasure and pride of reading to themselves.

When I leave a store I tend to thank the shopkeeper but as I leave the bookshop this morning I pause for another moment on the stairs, then sneak quietly out the door. Her story is yet unfinished, the children still enjoying the sound of their language on the competent tongue of their mother as it mingles with their laughter.