Panama City—The sleek executive offices of ENSA, one of Panama’s largest electric distribution companies, are a world apart from the seaside city of Colón, where rotting buildings and open sewage are the backdrop for joblessness, poverty and violent crime.

The 100 or so ENSA employees who live in Colón struggle with more than just the hour-long commute. They constantly worry about their safety: about their kids falling into gangs or getting recruited to sell drugs; about someone attacking them for being one of the guys who shuts off the power when the payment is late.

“They have trouble just living there,” says Lorena Fabrega, ENSA’s customer services director. When the company started a volunteer program in Colón a decade ago, she had to bus employees from Panama City. Even staff who lived in Colón did not want to participate.

But evolving ideas about how to run a business is making the way ENSA interacts with communities like Colón an important part of its corporate identity. For it, and many other private sector companies in Panama, giving back and getting involved have become key marketing and recruiting strategies.

“It used to be that what’s good for the company is good for society, and now we see it as the inverse,” Fabrega says. “It’s what’s good for society ends up being good for the company.”

ENSA succeeded in reaching out to young people in poor, crime-affected areas in the company’s service area by partnering with Creative Associates International’s Panama Youth at Risk program, known locally as Alcance Positivo.

Targeting the most-vulnerable neighborhoods

The three-year program, funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development, cultivates violence prevention and positive youth development in Panama, especially through 23 youth outreach centers set up in some of its most vulnerable neighborhoods.

“The Outreach Centers really tie into Creative’s overall violence prevention strategy because they’re an anchor,” says Michael McCabe, who ran the project for the global development company.

In neighborhoods where families lived packed together, where gunshots rang out between rival gangs in the night, “you had this Outreach Center where kids knew they could come. They could suddenly let down their guard. They knew that there were adults who would listen to them that would care about what they’re doing.”

With some of the biggest names in business pledging support for these centers, these partnerships are benefitting both kids and corporations.

Panama is viewed as a success story in Central America, where it lives next to Colombia and down the street from internationally disturbing levels of homicide in Honduras and El Salvador.

Despite its double-digit economic growth, gleaming new skyscrapers and expanding Canal Zone, Panama has endemic pockets of poverty—one third of boys never go past the sixth grade, and a World Bank poverty analysis revealed Panama is one of the most unequal countries in the world.

“We have two Panamas: the rich Panama, and the poor Panama,” says Marcella Tejada, Corporate Social Responsibility Manager for the Morgan and Morgan Group—a major Panamanian law firm, which supports the Outreach Centers.

“Most people, we live parallel lives,” she says. “I had no idea how many young kids had abandoned school and had no dream for the future…They have no plans. How can that happen?”

According to Panama’s former President and Minister of Education Aristides Royo, who is also a senior partner at Morgan and Morgan, the problem stems in part from the country’s low-quality education and the lack of real skills it provides students.

Children leave school because they need to earn money for their families, which are often run by single moms, or because they don’t see the value in education when it comes to finding work.

“They see a future so long and so difficult,” says Royo, who blames poverty and the long stretches of non-constructive time when mothers are at work and kids must entertain and fend for themselves.

When these children are approached by drug dealers hawking a lifestyle that includes a lot less deprivation, it’s an easy sell.

Companies helping kids look forward

Alcance Positivo partnered with private sector companies and NGOs to make it just as easy for young people in Panama to look forward to a meaningful, productive adulthood.

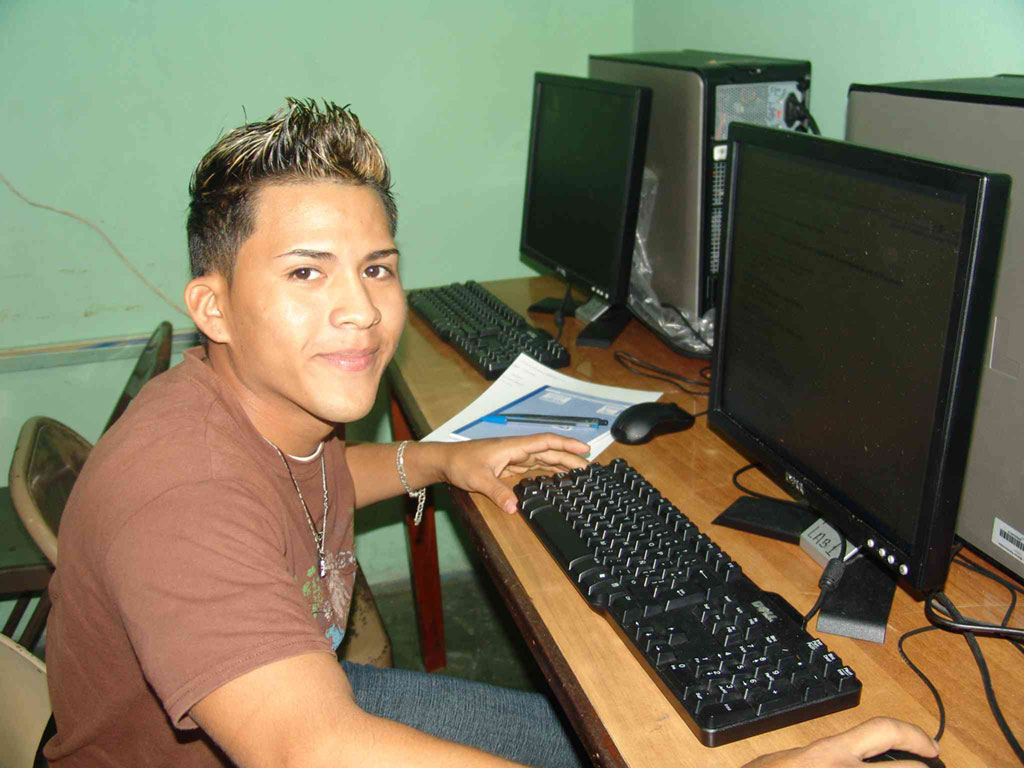

Business like Microsoft, Dell and Copa Airlines provided funding and equipment for the Outreach Centers, while employee volunteers also provided job skills training, facilitated workshops on dating violence, and simply showed up to make it clear to kids that they cared.

“By having them work both as volunteers and providing resources, they built a relationship that we hope will last many years beyond just the initial two-year agreement period,” says McCabe.

ENSA employees, for example, provided lighting that helped turn the Samaria Outreach Center in San Miguelito into an InfoPlaza, a science and technology center supported by the government. They teach young people at the centers how to use energy efficiently and mitigate risks.

Morgan and Morgan brought in a psychologist to train 20 of its employees on running domestic violence prevention workshops at the Outreach Centers.

They worked with 130 kids before Creative’s Alcance Positivo ended in September 2013, but Tejada has no intention of stopping just because the project did. She is already brainstorming how the firm can expand to reach all of the centers.

“We cannot think that the only scope as lawyers will be winning money,” says Royo. “We have to help society because society becomes better…It’s making better the future of Panama; making better citizens, making better boys. In this field I cannot think as a politician. I am thinking as a Panamanian citizen, as a father of three kids and grandfather of seven people. We have to think of our nation.”

“By having them work both as volunteers and providing resources, they built a relationship that we hope will last many years beyond just the initial two-year agreement period,” says McCabe.

ENSA employees, for example, provided lighting that helped turn the Samaria Outreach Center in San Miguelito into an InfoPlaza, a science and technology center supported by the government. They teach young people at the centers how to use energy efficiently and mitigate risks.

Morgan and Morgan brought in a psychologist to train 20 of its employees on running domestic violence prevention workshops at the Outreach Centers.

They worked with 130 kids before Creative’s Alcance Positivo ended in September 2013, but Tejada has no intention of stopping just because the project did. She is already brainstorming how the firm can expand to reach all of the centers.

“We cannot think that the only scope as lawyers will be winning money,” says Royo. “We have to help society because society becomes better…It’s making better the future of Panama; making better citizens, making better boys. In this field I cannot think as a politician. I am thinking as a Panamanian citizen, as a father of three kids and grandfather of seven people. We have to think of our nation.”

Good for the company & youth

Corporate social responsibility makes good business sense too: Employees with a sense of well-being are more productive at work and probably more likely to stay with the company—important in a country like Panama where unemployment is very low.

“We have measured the rotation of people that are volunteers versus the ones that are not volunteers and it’s proven that the ones that are volunteers have a better sense of belonging,” Tejada says.

Employees these days don’t just want a paycheck, she points out. They want to give back. And by developing their leadership skills and teamwork through volunteering, they become better employees overall.

Working with Alcance Positivo helped these companies develop potential future employees by providing at-risk students with job preparedness training, computer skills, and increased confidence.

Then there are the major benefits for companies that manage to build good relationships with communities.

“If you have a safer place to work, your employees are going to be motivated, they’re going to work a lot better, and it’s going to be good for the company,” says ENSA’s Fabrega. “If you have a community that can relate to you, that appreciates you, it’s going to be a lot easier to do your job.”

And being visible in the community in such a positive way is some of the best publicity a company can get.

ENSA wants to work with all of the communities in its service area, and the 13 Outreach Centers in Colón, Panama City, San Miguelito and 24 Diciembre are an obvious access point.

By partnering with the centers, ENSA is able to reach precisely those young people it needs to: those in areas rife with delinquency and safety issues, whose families are most likely to use energy without paying and set up illegal connections that not only hurt ENSA’s bottom line but cause dangerous accidents.

“The main objective is to help the youth when they’re at a stage in their lives when you can still make a difference in their habits,” says Fάbrega.

A Profitable Future

The habits youth are forming at the Outreach Centers go well beyond being good energy consumers. They are starting to think of themselves as people who can make a difference in their communities. They are envisioning futures that don’t include drugs and guns but classes and jobs. They are envisioning futures, period.

And so are the companies that got involved with Alcance Positivo. In coordination with the United Way of Panama, ten of the major businesses have created a matching fund and are committed to sustaining the Outreach Centers for another two years beyond the project’s end.

In that time, they’ll be working to help the centers build up their own sustainability.

ENSA, for instance, donated the $16,000 proceeds from their annual walkathon so that the Outreach Center in Colón could buy silk-screening equipment. Besides learning new skills and offering a service to the community, proceeds from the microenterprise will help the center stay open.

“Eventually, hopefully, they won’t need much more sponsorship from companies…but they’ll be able to sustain themselves,” says Fabrega. “And that’s, I think, everybody’s mission when they participate in corporate social responsibility programs.”